Interview with Leonardo da Vinci

I told him that creative people sometimes accomplish the most when they work the least. Our minds are filled with ideas, and we need time for those ideas to marinate, until we eventually get an insight.

Leonardo da Vinci is the definition of a Renaissance man. His most famous works are the Mona Lisa and The Last Supper, but that’s barely the tip of the iceberg.

He made designs for a scuba diving suit, a parachute, a tank, and a flying machine. He pioneered new painting techniques like sfumato and acuity perspective. He did research in a wide variety of fields from astronomy to urban planning. He excelled at music and stand-up comedy.

He was the most curious man in history.

In this interview, I talk to Leonardo about learning, curiosity, creativity, and more.

(This is a historically accurate interview with Leonardo based on his notebooks, and the biography by Walter Isaacson. His responses are either based on his writings, or research by Isaacson. Citations are included so you can see the source for each response.)

DKB: Did you struggle with perfectionism?

Leonardo: I wouldn’t use the word “struggle” but yes, I always strived to bring my paintings as close as possible to perfection. That’s why I held on to some of them for decades.

There’s a painting I started in 1480 called “Saint Jerome in the Wilderness”, and at that point I didn’t know as much about human anatomy. I did some intense anatomy studies in 1510, and realized that one of the neck muscles in this painting was wrong, so I went back to correct it.1

I held on to my paintings because there was always the possibility that I’d discover a new way to improve them.

And when it felt like perfection was impossible for a painting because of the complexity, I abandoned it. Better to leave it unfinished, than make something I wasn’t proud of.2

DKB: How were you able to make so many new discoveries in such a wide variety of fields?

Leonardo: Above all, I was committed to being a disciple of experience.

Those arrogant, traditionally educated people might say that my work can’t be trusted because I didn’t go through the education system. That’s a bad take, because my subjects require real experience, not just the words of others.3

It’s true that I don’t have the power to regurgitate what someone else told me, like these “educated” people do. Instead I have something more powerful, the ability to come up with my own experiments and learn from nature directly.

When I was studying the flight of birds, I made detailed drawings of their anatomy, and ran experiments to understand their interaction with air.

If I went to school, I would have learned Aristotle’s thoughts on the flight of birds, which is that they were supported by air the same way that ships were by water. This is obviously wrong, because birds are heavier than air and subject to being pulled down by gravity.

From my own experiments, I learned that birds flew because of the difference in air pressure between the top and bottom of their curved wings. And with that knowledge, I was one step closer to building my flying machine.

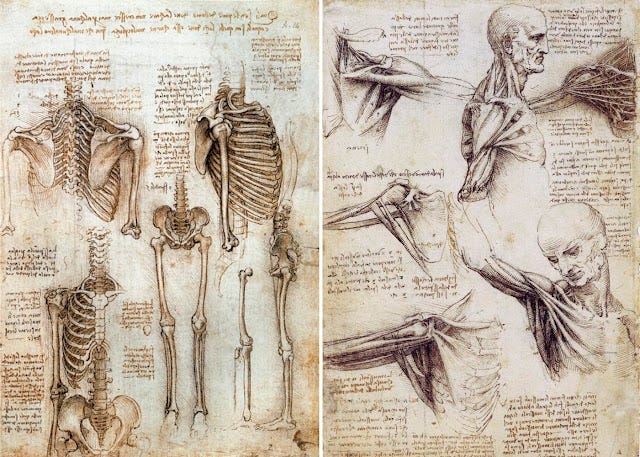

When it comes to representing the human form, most people only know surface level anatomy. I dissected bodies myself to understand every tiny detail of how they work. And when I was working on a horse sculpture, I dissected horses as well, and made comparisons with human anatomy.4

Alberti’s book on painting taught that lines should be drawn to delineate edges, and that’s what everyone did. I observed the real world and saw that it was the opposite. When we look at objects, we don’t see sharp lines around them, it’s a little blurry. That’s how I came up with the sfumato technique, where outlines have a smokey finish.5

DKB: It seems a bit crazy that you dissected horses to understand their anatomy better just to make a sculpture. Wouldn’t regular observation have been enough?

And likewise with human anatomy, I don’t see how understanding the heart or the brain would ever help you make better paintings.

Leonardo: With the horse sculpture I definitely got sidetracked. The purpose of the sculpture was to honor one of the previous Dukes by portraying him on a horse. But I got so obsessed with horses, I forgot all about the Duke.

I went so deep down the rabbit hole of horse anatomy that I started writing a book about it. I also thought of ways to make cleaner horse stables, and came up with new systems for replenishing the feed bins and removing manure.6

Was all of that “necessary” to make the horse sculpture? Absolutely not.

Often I would start learning something for a specific project, then end up falling down a rabbit hole along the way.

When I was studying human anatomy, I made detailed diagrams of the vertebrae, and investigated how the heart valves work. I don’t think any of this was particularly useful for painting, but I found it interesting.7

All the great people who came before me already figured out the useful and important things. So all that was left for me to study were the topics that others in the past saw and ignored because they didn’t seem important.8

People who only care about money might call this useless work, but I believe that wisdom is the highest good. Nothing is more fundamental to a healthy soul.9

DKB: You clearly learned a lot through your own observations and experiments, but I’m curious about the importance of other people in your journey.

Were you a lone genius? How important was collaboration for you?

Leonardo: I wouldn’t have gotten anywhere without the help of some amazing people. In the Milanese court, I was surrounded by the smartest people in a wide variety of fields. We had musicians, engineers, and all kinds of scientists. It was heaven.10

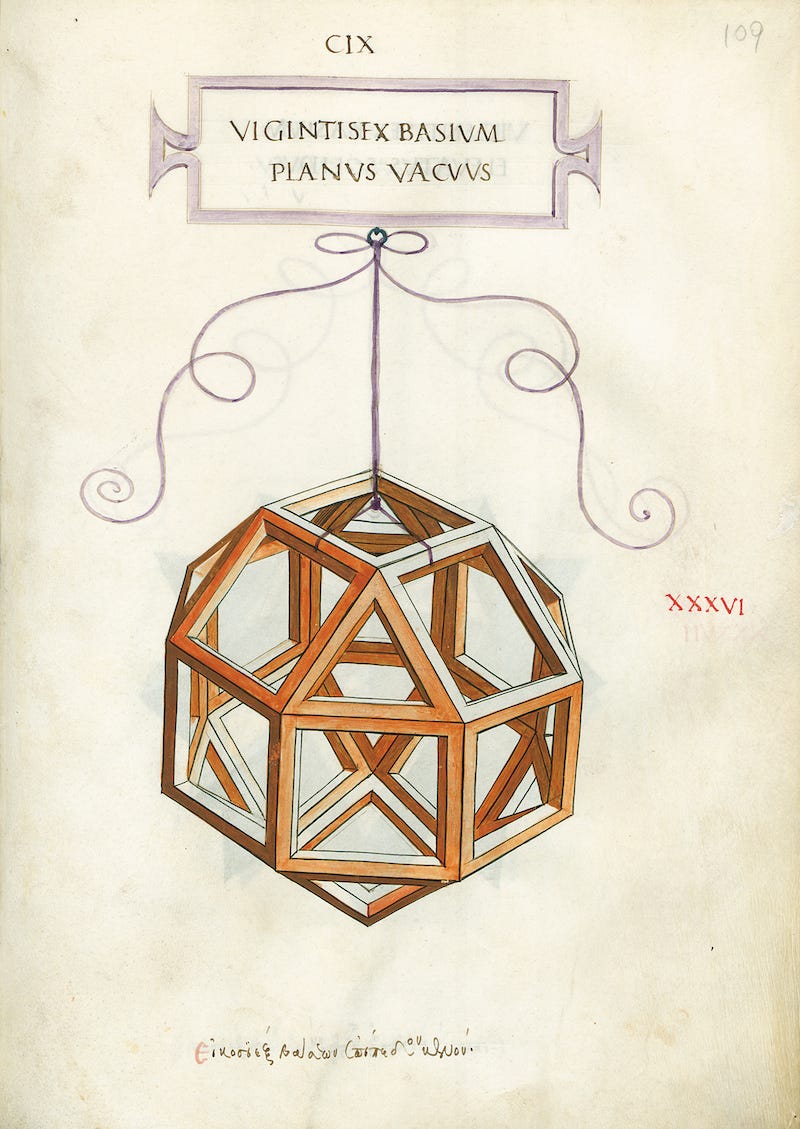

One of my closest friends at the Milanese court was Luca Pacioli, a great mathematician. He taught me the beauty of geometry and other math concepts, and I worked on the shape illustrations for his math book.11

With the help of Marcantonio della Torre, a university professor, I was able to illustrate and describe every muscle group and major organ of the human body. There’s no way I would have been able to do this on my own.12

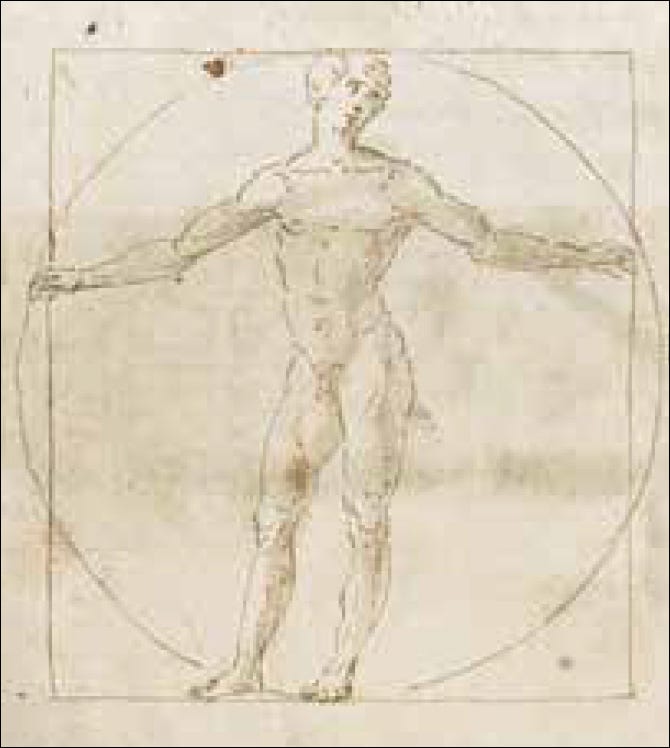

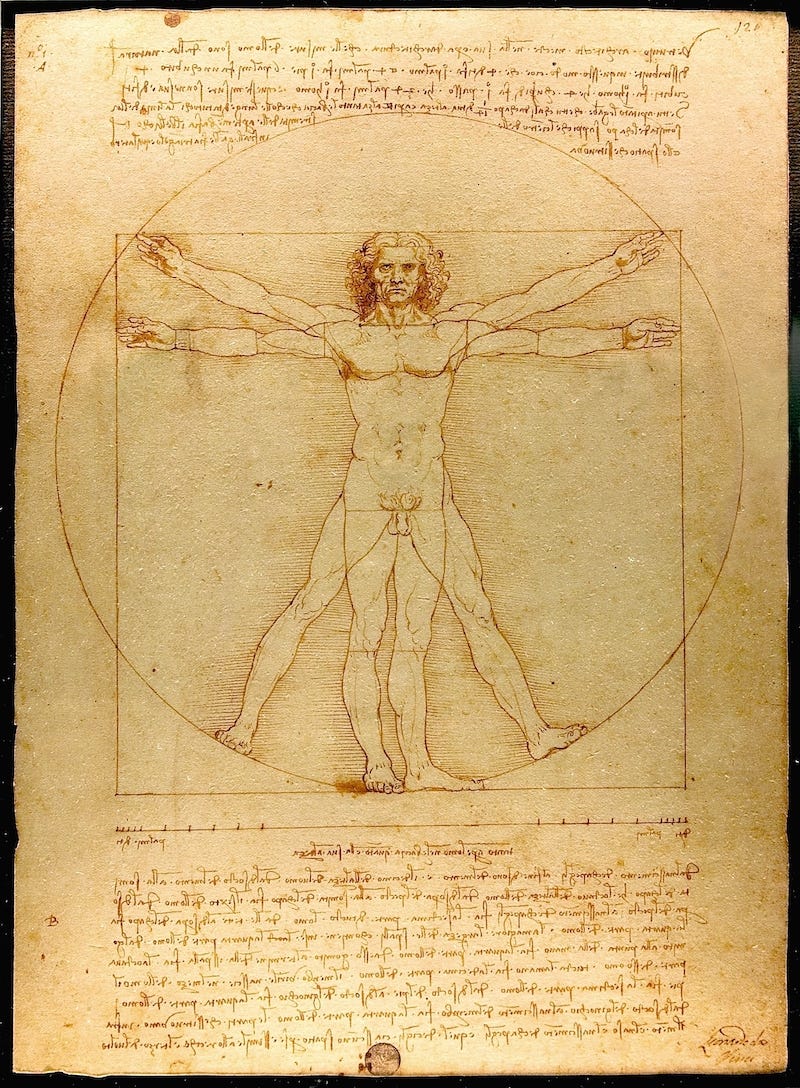

My “Vitruvian Man” drawing was the result of bouncing ideas around with my friends Francesco and Giacomo.

For context, Vitruvius was an old architect who had this idea that the layout of a template should reflect the proportions of the ideal human body. He described a way to draw a man in a circle and square to determine the ideal proportions for a temple.

In a temple there ought to be harmony in the symmetrical relations of the different parts to the whole. In the human body, the central point is the navel. If a man is placed flat on his back, with his hands and feet extended, and a compass centered at his navel, his fingers and toes will touch the circumference of a circle thereby described. And just as the human body yields a circular outline, so too a square may be found from it. For if we measure the distance from the soles of the feet to the top of the head, and then apply that measure to the outstretched arms, the breadth will be found to be the same as the height, as in the case of a perfect square. – Vitruvius, De architectura

Here are some drawings of Francesco’s thoughts13:

And here are Giacomo’s thoughts:

All of our discussions were very helpful, and I was able to make a version that I was proud of.

DKB: Can you talk briefly about your creative process when it comes to paintings?

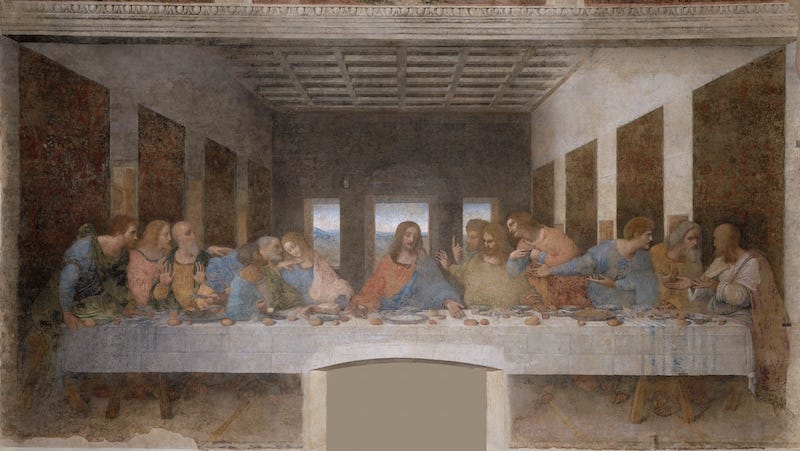

Leonardo: The story of The Last Supper is pretty funny. I had to paint that one in public, so there were people who would come every day to see what I was doing.14

Some days I would go early in the morning, climb the scaffolding, and paint all day without moving to eat or drink.

Other days I would go there and stare at the painting for hours, looking for flaws and opportunities for improvements. Then I would leave without painting anything.

Sometimes I would suddenly have a new insight, go to the painting, climb the scaffolding, apply a single brush stroke, then leave.

The Duke of Milan heard about this stuff and was worried I wouldn’t finish the painting on time. I had a discussion with him about how creativity worked.

I told him that creative people sometimes accomplish the most when they work the least. Our minds are filled with ideas, and we need time for those ideas to marinate, until we eventually get an insight.

I also told him I had two heads left to paint: Christ and Judas. And I was having trouble finding a model for Judas, so he could be the model if he really wanted it done right now. Then he laughed and sent me away.

DKB: Did you have any low points on your journey?

One of the darkest periods of my life was right before my 30th birthday. I had been working hard for so many years, but all I had to show for it was some unfinished paintings, and contributions to generic artwork that the workshop churned out to make money.

I hadn’t really accomplished anything, and it was depressing.

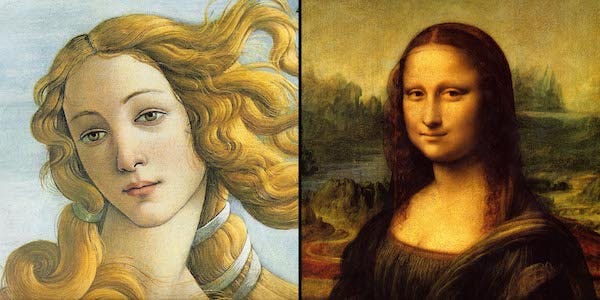

Meanwhile other artists like Botticelli were gaining traction. He got commissions from the Medici, and was invited by the Pope to add paintings to the Sistine Chapel, along with other famous artists. They didn’t even consider inviting me.

There was no hope left for me in Florence, so I set my sights on Milan, moving there with the hope of making the Duke my patron.

Unlike Florence, Milan didn’t have many good artists, so I knew it would be easier to stand out. It was also filled with intellectuals from a wide variety of fields thanks to the nearby university, so I figured I’d be able to learn a lot.

The Milan move ended up working out, but I’ll never forget those depressing last days in Florence.

DKB: How did you get your first patron?

I knew that the Duke of Milan was filled with military ambition. His family had taken Milan by force, and faced the constant threat of revolt or invasion. So I crafted a letter that I knew would get his attention.

Most illustrious Lord,

Having now sufficiently studied the inventions of all those who proclaim themselves skilled contrivers of instruments of war, and having found that these instruments are no different than those in common use, I shall be bold enough to offer, with all due respect to the others, my own secrets to your Excellency and to demonstrate them at your Convenience.

1) I have designed extremely light and strong bridges, adapted to be easily carried, and with them you may pursue and at any time flee from the enemy; and others, indestructible by fire and battle, easy to lift and place. Also methods of burning and destroying those of the enemy.

2) I know how, during a siege, to take the water out of the trenches, and make an infinite variety of bridges, covered ways, ladders, and other machines suitable to such expeditions.

3) If a place under siege cannot be reduced by bombardment, because of the height of its banks or the strength of its position, I have methods for destroying any fortress even if it is founded upon solid rock.

4) I have kinds of cannons, convenient and easy to carry, that can fling small stones almost resembling a hailstorm; and the smoke of these will cause great terror to the enemy, to his great detriment and confusion.

5) And when the fight is at sea, I have many kinds of efficient machines for offense and defense, and vessels that will resist the attack of the largest guns, and powder and fumes.

6) I have ways of making, without noise, underground tunnels and secret winding passages to arrive at a desired point, even if it is necessary to pass underneath trenches or a river.

7) I will make unassailable armored chariots that can penetrate the ranks of the enemy with their artillery, and there is no body of soldiers so great that it could withstand them. And behind these, infantry could follow quite unhurt.

8) In case of need I will make cannons and artillery of beautiful and useful design that are different from those in common use.

9) Where bombardment will not work, I can devise catapults, mangonels, caltrops and other effective machines not in common use.

10) In times of peace I can give perfect satisfaction and be the equal of any other in architecture and the composition of buildings public and private; and in guiding water from one place to another.

Also, I can execute sculpture in marble, bronze and clay. Likewise in painting, I can do everything possible, as well as any other man, whosoever he may be.

Moreover, work could be undertaken on the bronze horse, which will be to the immortal glory and eternal honor of His Lordship, your father, and of the illustrious house of Sforza. And if any of the above-mentioned things seem impossible or impracticable to anyone, I am most readily disposed to demonstrate them in your park or in whatsoever place shall please Your Excellency.

I barely even mentioned painting. I talked about my experience as an accomplished weapons designer, and shared some of my latest military ideas. This was all a bit of an exaggeration, since I never actually made any weapons, but I needed to get my foot in the door somehow.

And it worked.

DKB: Do you have any last words of wisdom?

Leonardo: Just like a day well spent brings happy sleep, a life well used brings happy death.15

Use your life well.

Follow your curiosities, dive down rabbit holes, and make something you’re proud of.

"He posited that the painting was done in two phases, the first around 1480 and the other following the dissection studies he made in 1510. Clayton’s theory was supported by infrared analysis, which showed that the dual neck muscles were not part of the original underdrawing and that they were painted with a technique different from the other parts. “Significant parts of the modeling of the Saint Jerome were added twenty years after his first outlining of the figure,” said Clayton, “and that modeling incorporates the anatomical discoveries that Leonardo made during his dissections of the winter of 1510.”" ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 3, Saint Jerome in the Wilderness)

"As Vasari explained about Leonardo’s unfinished works, he was stymied because his conceptions were “so subtle and so marvelous” that they were impossible to execute faultlessly. “It seemed to him that the hand was not able to attain to the perfection of art in carrying out the things which he imagined.” According to Lomazzo, the other early biographer, “he never finished any of the works he began because, so sublime was his idea of art, he saw faults even in the things that to others seemed miracles.”" ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 3, Abandoned)

"I am fully aware that the fact of my not being a man of letters may cause certain presumptuous persons to think that they may with reason blame me, alleging that I am a man without learning. Foolish folk! Do they not know that I might retort by saying, as did Marius to the Roman Patricians: ‘They who adorn themselves in the labours of others will not permit me my own.’ They will say that because I have no book learning, I cannot properly express what I desire to treat of—but they do not know that my subjects require for their exposition experience rather than the words of others. Experience has been the mistress of whoever has written well; and so as mistress I will cite her in all cases.

Though I have no power to quote from authors as they have, I shall rely on a far bigger and more worthy thing—on experience, the instructress of their masters. They strut about puffed up and pompous, decked out and adorned not with their own labours, but by those of others, and they will not even allow me my own. And if they despise me who am an inventor, how much more should they be blamed who are not inventors but trumpeters and reciters of the works of others." ("Notebooks (Oxford World's Classics)", Leonardo da Vinci, Chapter 1, Section 1)

"This eventually leads him into comparative anatomy; in a later set of drawings of human anatomy, he renders the muscles, bones, and tendons of a man’s left leg next to those of a dissected back leg of a horse." ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 9, Designing The Monument)

"This theory—based on a Leonardesque blend of observation, optics, and mathematics—reinforced his belief that artists should not use lines in their paintings. “Do not edge contours with a definite outline, because the contours are lines, and they are invisible, not only from a distance, but also close at hand,” he wrote. “If the line and also the mathematical point are invisible, the outlines of things, also being lines, are invisible, even when they are near at hand.” Instead an artist needs to represent the shape and volume of objects by relying on light and shadow. “The line forming the boundary of a surface is of invisible thickness. Therefore, O painter, do not surround your bodies with lines.” This was an upending of the Florentine tradition known as disegno lineamentum, praised by Vasari, which was founded on linear precision in drawing and the use of lines to create forms and designs." ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 17, Shapes Without Lines)

"Leonardo got so deeply immersed in these studies that he decided to begin an entire treatise on the anatomy of horses. Vasari claimed that it was actually completed, though that seems unlikely. As usual, Leonardo was easily distracted by related topics. While studying horses, he began plotting methods to make cleaner stables; over the years he would devise multiple systems for mangers with mechanisms to replenish feed bins through conduits from an attic and to remove manure using water sluices and inclined floors." ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 9, Designing The Monument)

"Leonardo’s greatest achievement in his heart studies, and indeed in all of his anatomical work, was his discovery of the way the aortic valve works, a triumph that was confirmed only in modern times. It was birthed by his understanding, indeed love, of spiral flows." ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 27)

"Seeing that I cannot find any subject of great utility or pleasure, because the men who have come before me have taken for their own all useful and necessary themes, I will do like one who, because of his poverty, is the last to arrive at the fair, and not being able otherwise to provide for himself, takes all the things which others have already seen and not taken but refused as being of little value; I will load my modest pack with these despised and rejected wares, the leavings of many buyers; and will go about distributing, not indeed in great cities, but in the poor hamlets, taking such reward as the thing I give may be worth." ("Notebooks (Oxford World's Classics)", Leonardo da Vinci, Chapter 1, Section 1)

"I know that many will call this useless work . . . men who desire nothing but material riches and are absolutely devoid of that of wisdom, which is the food and only true riches of the mind. For so much more worthy as the soul is than the body, so much more noble are the possessions of the soul than those of the body. And often, when I see one of these men take this work in his hand, I wonder that he does not put it to his nose, like a monkey, or ask me if it is something good to eat." ("Notebooks (Oxford World's Classics)", Leonardo da Vinci, Chapter 6, Section 3)

"In addition to the troupes of musicians and pageant performers, those on stipend at the Sforza court included architects, engineers, mathematicians, medical researchers, and scientists of various stripes who helped Leonardo with his continuing education and indulged his insatiable curiosity." ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 8, Collaboration and Vitruvian Man)

"More seriously, Leonardo learned math from Pacioli, a great tutor, who taught him the subtleties and beauties of Euclid’s geometry and tried to teach him, with less success, how to multiply squares and square roots. At times when he found a concept difficult to comprehend, Leonardo would copy passages of Pacioli’s explanations verbatim into his notebooks. Leonardo returned the favor by drawing a set of mathematical illustrations, of astonishing artistic beauty and grace, for the book Pacioli began writing upon his arrival in Milan, On Divine Proportion, which examines the role of proportions and ratios in architecture, art, anatomy, and math. Given Leonardo’s appreciation for the intersection of arts and sciences, he was fascinated by the topic." ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 13, Luca Pacioli)

"But, true to form, Leonardo preferred learning from experiment rather than from established authority. His most important hands-on inquiries came during the winter of 1510–11, when he collaborated with Marcantonio della Torre, a twenty-nine-year-old anatomy professor at the University of Pavia. “Each helped and was helped by the other,” Vasari wrote of their relationship. The young professor provided the human cadavers—probably twenty of them were dissected that winter—and lectured while his students did the actual cutting and Leonardo made notes and drawings." ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 27, Dissections)

"It was a powerful image. But as far as we know, no one of note had made a serious and precise drawing along these lines in the fifteen centuries since Vitruvius composed his description. Then, around 1490, Leonardo and his friends proceeded to tackle this depiction of man spread-eagle amid a church and the universe." ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 8)

"When Leonardo was painting The Last Supper, spectators would visit and sit quietly just so they could watch him work. The creation of art, like the discussion of science, had become at times a public event. According to the account of a priest, Leonardo would “come here in the early hours of the morning and mount the scaffolding,” and then “remain there brush in hand from sunrise to sunset, forgetting to eat or drink, painting continually.” On other days, however, nothing would be painted. “He would remain in front of it for one or two hours and contemplate it in solitude, examining and criticizing to himself the figures he had created.” Then there were dramatic days that combined his obsessiveness and his penchant for procrastination. As if caught by whim or passion, he would arrive suddenly in the middle of the day, “climb the scaffolding, seize a brush, apply a brush stroke or two to one of the figures, and suddenly depart.”" ("Leonardo da Vinci", Walter Isaacson, Chapter 18, The Commission)

"As a day well spent brings happy sleep, so a life well used brings happy death." ("Notebooks (Oxford World's Classics)", Leonardo da Vinci, Chapter 6, Section 1)